A History of Ashburton’s Green Spaces

- scraze

- Mar 28, 2022

- 23 min read

Recently, I’ve begun doing some research for the Ashburton Willows Cricket Club. My role in the research is more on the “Ashburton” side than the “Cricket” so part of it has involved trawling through City of Camberwell Council records at the Public Records Office in North Melbourne. As this photograph shows, this is as exciting as it looks. All I can say is thankfully the pages within these volumes are typed and indexed. The illusion of my glamorous life as a local historian remains intact.

The Green Spaces of Boroondara

The City of Camberwell records have allowed me to gain insight into the development of Ashburton’s green spaces. Around 19 per cent of Melbourne is green space. This is good in comparison to Adelaide, Brisbane and Sydney but less than half of the green space in less populated capitals.

Within Melbourne, Boroondara is known as a very leafy and green district. Fortunately for us, Ashburton has by far the highest amount of public green space available per capita. See the chart below for comparisons.

Suburb | Space per Sqm |

Surrey Hills | 8.48 |

Kew | 14.35 |

Burwood | 14.67 |

Hawthorn East | 15.77 |

Camberwell | 18.38 |

Hawthorn | 19.36 |

Glen iris | 19.93 |

Canterbury | 23.61 |

Ashburton | 25.48 |

Today, Ashburton has five Reserves: Ashburton Park, Dorothy Laver Reserve East, Markham Reserve, Warner Reserve, and Watson Park. There are also several on the suburb’s periphery, such as Burwood Reserve, Hartwell Sports Ground, and Eric Raven Reserve; and the Outer Circle Trail, Anniversary Trail and Gardiner’s Creek Trail that pass through the suburb.

What is interesting about that 25.48 sqm per capita is that for decades in Boroondara’s early history, Ashburton suffered from a severe case of civic neglect.

The story of how this came about turned out to be very interesting.

If you don’t want the history and are just after the information on reserves, here are some quick links to the reserves mentioned in this post:

The ‘civic neglect’ of Ashburton by the City of Camberwell Council (1890-1935)

When Australia federated, there had already been various colonial governments in place for over a century. Immigrant Australian citizens gained the ingrained expectation that our Governments will always provide for us in return for our tax dollars. In the 1920s, this expectation tended to conflict with the reality of the motivations of the men who sat on local councils: wealthy capitalist landowners.

Since its first settlement in the 1890s, Ashburton was part of the City of Camberwell. Situated on the far-eastern boundary, it fell under the Council’s South Ward. Admittedly, this was a sparsely populated area for many years. But from the 1920s, the population began to rapidly grow.

South Ward’s new residents did what Australians always do: they expected the local government to provide a return for their taxes and rates. The City Councillors were certainly not sitting idly by: the records show drainage works, street repair, fencing, reticulation, infectious disease control, and tree-planting occurred in Balwyn, Camberwell and Canterbury. But when it came to South Ward – Burwood, Glen Iris, and Ashburton – there is very little mention of anything at all.

In June 1932, Councillor Nettleton (of Nettleton Park fame), lamented that ‘we have purchased throughout Camberwell 265 acres for parks and playgrounds but not one acre of it is in Ashburton. I do not pretend to know the value of the land but I do know that Ashburton must have a playground.’[1]

He was referring to the Council's rejection of a below market value offer of seven acres of Ashburton land for a park and play area. It turns out the few Councillors who did support Ashburton’s green space development are recognisable today because, like Nettleton, they now have a local park named after them.

The Council’s neglect did not go unnoticed by Ashburton’s early residents.

‘Despite numerous complaints, no action has been taken to deal with straying cattle,’ wrote ‘Squatter’ to the Argus on 21 June 1935. ‘The drains adjacent to the station are a menace to the health of the community.’ Replied ‘Ratepayer’ in response, ‘’Squatter’s’ complaint is echoed by many. Camberwell Council stays progress by its civic neglect. Under the unimproved rating system the council has been collecting high rates from sub-divisional blocks east from the station for 10 years. Surely the total collected during that period should warrant some civic progress in the district?’

The rise of the Progress Associations

The 1920s were a time of increasing economic and social power among the middle and working classes. For the first time, they were able to purchase small areas of land and build homes, in direct contrast to the established wealthy landowners who owned large swathes of land in the area (as you can see in the map above). These men sat on the Council or held significant influence with it, and they controlled the provision of roads, sanitation, drainage and lighting around the new properties. If the new residents wanted their street sealed and their waste dealt with, they needed to unite and lobby the Council. So many new landowners in Melbourne, Glen Iris and Ashburton residents formed a Progress Association.

In the 1920s, the Ashburton Progress Association had some small wins – a few street lights and some improved drainage on High Street. But as the correspondence referred to above attested, there was still little change well into the 1930s. They had even less success in obtaining land for public reserves. When it came to green spaces for recreation and enjoyment in Glen Iris and Ashburton’s early years, the driving force was certainly not the City of Camberwell Council.

For those residents that did manage to obtain a reserve, costs and maintenance of them fell to them. They would form committees and then go into battle with the Council to squeeze out funds to provide drainage, fencing, sheds, and pavilions. For many years, the Council only agreed to fund facilities if the residents shared the costs with them. It could take several years to acquire the funding for a pavilion. Sometimes Committees eventually achieved a standing maintenance fee, although were forced to write several letters a year asking for its payment.

The impact of the Great Depression

Then in 1934, Camberwell Council shifted its position on reserves. It was now the height of the Great Depression and widespread unemployment and poverty abounded. Governments across the world were funding projects to provide employment and stimulate the deflated economy. Perhaps the Council realised that investing in the area’s much neglected sports grounds recognised the important role of sport in providing hope and escape for people in a time of despair.

New councillors decided to take on more financial responsibility for maintaining green space. In November 1934, they announced an £8,000 investment project to improve the area’s local parks. A very small portion went to the parks around the Ashburton, Burwood and Glen Iris but at least half of the funding went to the Camberwell Sports Ground for a new pavilion and other improvements.

The Council faced vocal criticism from the Ashburton Progress Association over the decision to also expend £12,000 on a new Town Hall when a lack of adequate drainage had caused Chaleyer Street to become a cesspit of disease. In an extraordinary move, the APA publicly criticised the Council. At the meeting, Councillor Warner – who would go on to have his own Ashburton reserve named after him – did acknowledge Ashburton’s neglect. However he ‘deplored the manner in which the correspondence was submitted.’[2]

Nevertheless, the Association’s point was made. From that time on, City of Camberwell Council began investing in Ashburton, including the suburb’s parks and reserves.

The ban on sport on Sunday

As this shift in its economic priorities was occurring, the Council was standing its ground on another: its adamant refusal to allow any sport to be played on Sunday. In 1936, the Council passed a by-law expressly prohibiting it. The leader of the Protestant Church community, led by Mr W Gordon Sprigg (who lived in Florizel Street), lobbied hard against the idea. ‘Sunday,’ he argued, ‘was a day kept solely for God’.[3]

This was a disaster for the Committees of the local reserves. Sunday sport would allow more sports and games to be played (by boys and men, not girls and women) , leading to more attendance revenue, and therefore more cash to spend on maintaining and improving the Reserves. There was definitely support for over-turning the ban within the community, especially among the non-voting young people. So the Council proposed a plebiscite (remember that?!) on the subject in 1946. The meagre vote of only 25 per cent of residents came back ‘No’.[4]

A month later, Cr J S August, a firm ‘Yes’ advocate, moved a motion to permit non-commercialised sport in the municipality. He argued the plebiscite results did not accurately reflect the views of Camberwell. But he got nowhere against the religious lobby and the establishment of the Council.

Meanwhile, change was occurring across Melbourne. The residents of Coburg voted a resounding ‘Yes’ to Sunday sport. So had the Melbourne City Council, Heidelberg, and St Kilda Councils. Other councils had a hybrid-type model; some ‘gentle’ sports like golf, bowls and tennis were fine, others prohibited. Only in Camberwell, Box Hill, Prahran, and Sandringham was Sunday sport prohibited outright.

Eventually the Church recognised that sport provided a much needed outlet for young people, who were otherwise idle and prone to mischief. In 1959, the Youth Christian Workers (all boys) began a campaign to allow non-commercialised sports to be played on Sunday. Camberwell became a key battleground. They successfully managed to lobby for another referendum, arguing that vandalism and delinquency were at their worst on Sunday afternoons because Camberwell youth were not permitted to use their energy for healthy recreation.

The Youth Christian Workers succeeded: the by-law was abolished that year.

[It’s at this point I have to stop because due to maintenance needed at the State Library, there is currently no access to research resources from the 1960s-2000s. However, if anything really exciting happened, I will update the post accordingly.]

In 1994, City of Camberwell, City of Hawthorn, and City of Kew were combined to create Boroondara Council. In its 2021-22 budget, Boroondara allocated over A$10 million for maintenance of parks and reserves in the Council jurisdiction. One of its key objectives is to upgrade sports pavilions to provide changing rooms for girls.

The Reserves of Ashburton

So – how did Ashburton come to have the largest portion of green space in Boroondara when we already know that it was not driven by the City of Camberwell?

In the first instance, land came from private landowners who offered their paddocks unsuitable for grazing or farming for recreational use. Later, some offered their land for sale to the Council, usually at far below its market value. Sometimes these offers were accepted, other times not. After the Council acquired land for Reserves, nearby landowners occasionally offered parcels of their land to help extend the Reserve area. However, the largest of Ashburton’s green spaces – the swathe of Markham Reserve – came about purely because the Council neglected Ashburton. But I’ll get to that later.

Ashburton Forest

The most dominant landowner around Ashburton in the 1920s was Michael Mornane. Mr Mornane lived in East Melbourne and was a prominent Melbourne-born Catholic solicitor with a keen business sense.[1] According to his obituary, he was a generous man who disliked any attention given to his considerable charitable assistance. He was an enthusiastic follower of football, cricket and racing and this may have contributed to his generosity in providing land for Ashburton’s sporting culture. In the 1920s, Mr Mornane sold off a few paddocks for the creation of Summerhill Park and also donated the land for St Michaels Parish School. He refused any recognition of this generous action in his lifetime. He died in August 1931, aged 76.

Mr Mornane was also the owner of the 100+ acre land that formed the famous Ashburton Forest. This was one of the earliest locations for recreation in the area.

Once the ill-fated Outer Circle train line arrived at Ashburton, the Ashburton Forest became the premier weekend picnic spot for Melbourne residents. It used to stretch from High Street to Kooyong Koot (Gardiner’s) Creek in the west, towards Boundary (Warrigal) Road. In 1912, local residents lobbied the Tramway Board to extend the High Street to Boundary Road to help further develop the area further. This began a decades-long campaign that ultimately failed. According to local historian Neville Lee, at some point Mr Mornane offered the parcel of land for sale to Camberwell Council, but they rejected his offer as too expensive.

By the 1920s, more and more of the Ashburton Forest was being subsumed by suburban development. Some Melbournians despaired at the loss and hoped the land would become a permanent park. Wrote ‘Tree Lover’ in St Kilda on 14 July 1925:

‘This particular park, although privately owned, has always been well patronised by picnic parties during weekends and holidays... Several months ago, the Malvern City Council made a move towards purchasing this land, but owing to the high price demanded, no sale was made... If it is not too late, further efforts should be made to preserve land for the benefit of future generations.’

But it was not to be.

In 1926, the benevolent Mr Mornane sold a slice of Ashburton Forest to the Society for the Protection of Animals in Animal Welfare. They used the land to provide a rest home for overworked and toil weary horses. It was described as possessing ‘long vistas of grassy fields, watered by a little creek which meanders through the property, shaded by hedges of tea-tree and clumps of gum trees, flowering hawthorn bushes and other trees. In one part of the grounds there is a deep pool.’[2] The Rest Home lasted a few more years before eventually succumbing to developers.

Mr Mornane was also a known golf enthusiast. He established a nine-hole golf course on the land behind St Michael’s Parish. According to Neville Lee, it was a modest, quiet little course with rough and ready greens but it gave the feeling of being out in the country.[3] It was popular with the locals who devised innovative ways of avoiding paying the golf course fees. The course remained after Mr Mornane died until the last of his land was sold to the State Government for the Housing Commission Estate.

Today, very small pockets of the Ashburton Forest, consisting of original River Red Gums, remain at Ashburn Grove, Clifford Close, and along Welfare Parade. These are being carefully tended and regenerated by the Friends of Ashburton Forest with the support of Boroondara Council. The one pictured here is behind the new housing commission apartments being built on Markham Reserve.

Sherwood Park Racecourse

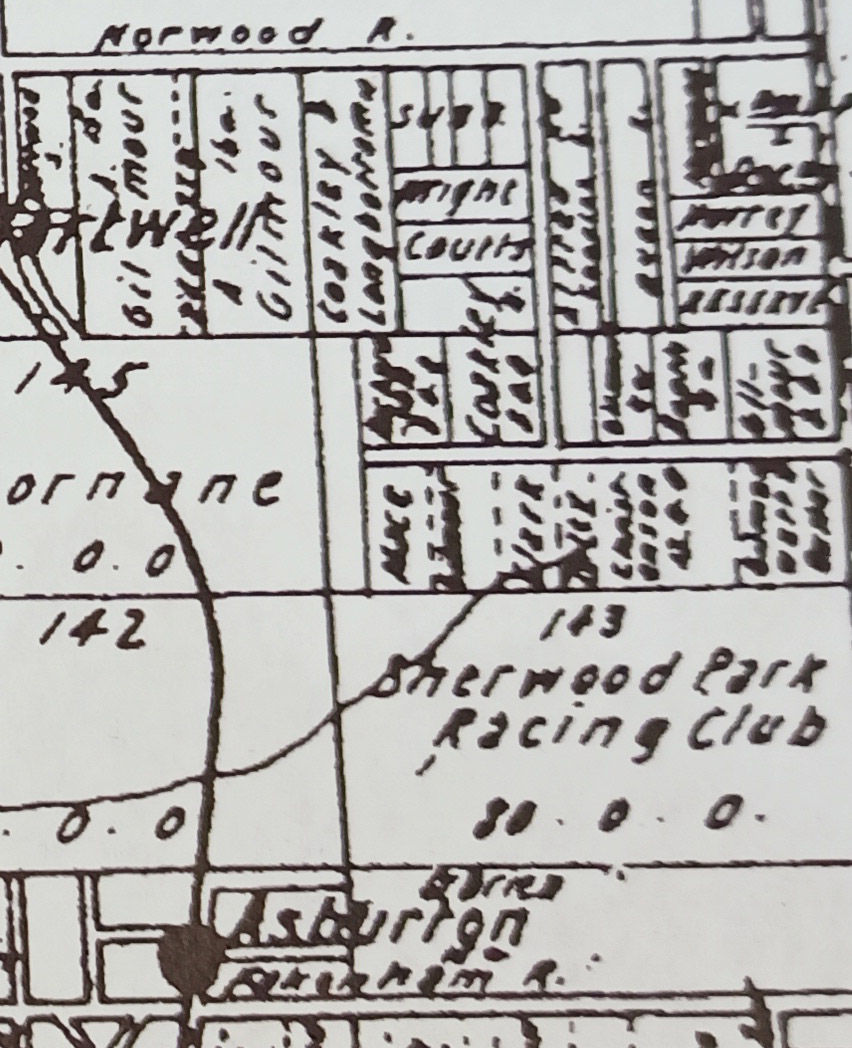

Situated somewhere between Liston Street and Norwood (Toorak) Road, the Sherwood Park Racecourse was a large, privately owned paddock used for horse racing from around 1888. Owned by Mr J B Scott, its surroundings were still rural, with a small local population.

By 1893, Melbourne’s economy boomed and the numerous racing events at Sherwood Park Races were well attended. Spectators could attend the races by catching the train to Camberwell and then a pleasant afternoon buggy drive. Mr Scott even rejected an offer of £40,000 for the site.[1]

The next year, the boom years were over. Few races were held and by 1895, the Victorian Racing Club had decided to hold more racing at Flemington. The Sherwood Park site was still used for athletics and cricket but there are few records of it being used at all after 1897.

Mr Scott then sold the land and all the racing improvements to Mr James Lindsay, a Malvern grocer for ‘a satisfactory figure of cash’.[2] Since no trace of it remains today, Mr Lindsay must have sold it off as sub-divisions.

Burwood Reserve

By far the oldest Council-owned reserve is Burwood Reserve. In 1907, the privately owned land was already in use as a local sports and recreation ground. Burwood residents, worried the ground could disappear at the whim of its owner, united and lobbied Camberwell Council to purchase the land. In November 1907, the residents of Burwood presented the South Ward representative Councillor Frederick Vear with a petition asking the Council to purchase four acres of the land that is now Burwood Reserve. In return, the residents proposed paying for the fencing and clearing of the land themselves. Cr Vear supported the proposal and the Council agreed to ask the State Government’s Minister of Lands for financial assistance to make the purchase.

Given all the money the City of Camberwell was spending in more populated areas under its remit, the Minister of Lands was not inclined to honour their request. But in an interesting twist, the next month he offered the Council £150 if they would also purchase eight acres of the nearby land known as ‘Fiddlers Green’ AND an additional 8 acres to Burwood Reserve. This was duly done.

In the Council’s ideological shift of 1934 towards funding more reserves, Burwood Reserve received £500 for grading, levelling and drainage.[3] This was a considerable chunk when compared to other parks, aside from Camberwell Sports Ground.

From then on, Burwood Reserve received a regular portion of funding for its maintenance. Its pavilion has been replaced at least twice and today it is the home of the Burwood Cricket Club, Ashburton United Junior Football Club, and St Mary's Salesian Amateur Football Club.

Ashburton Park

The Council’s rejection of the public push to purchase the Ashburton Forest parkland resulted in the purchase of a smaller parcel of Crown land on the corner of High Street and Vears Road in 1924.[4] Although the suburb was beginning to boom, it appeared few local residents were either willing or able to maintain the land. Ashburton’s Progress Association concentrated on more urgent matters; such as sanitation, drainage and the fruitless effort to push the tram tracks up High Street. From the Council’s end, little was done with Ashburton Park for around a decade.

During this time, Ashburton Willows records revealed the sheep, cows and horses grazing in the Park were pushed aside occasionally for a game of cricket. However, there is no record of a Cricket or Football Club seeking permission from the Council to use the land so it appears this was not done in any kind of organised club way. In 1933, a Park Management Committee appeared in the Council records but the Park did not receive a share of the £500 set aside for parks and reserves.

Thanks to the new Committee, Ashburton Park did receive £125 for park improvements in 1934. It spent this on several park benches. Six months after the Progress Association criticised the Council for neglecting Ashburton, Ashburton Park received a more significant funding boost of £500.[5] According to the Argus, the cash injections into the reserves were connected to improving the Council’s football grounds by providing better quality grass and fencing.

The money was also spent on planting the trees on the north and south ends. The Ashburton Progress Association told the Council it intended to call these areas ‘Warner Plantation North’ and ‘Warner Plantation South’ in honour of Cr Warner. Cr Warner was a well-known horticulturalist who owned a nursery in Burwood Road, Auburn.

The Ashburton Park Committee had finally learnt that if you name things in your park after a Councillor, you quickly get money for what you need.

The Cricket Club complained the lack of toilet facilities was holding back the Park’s development. So in 1936, the Committee proposed a pavilion for Ashburton Park to the Council. While this was received favourably, the next year, something had gone very wrong within the Park Committee. The records do not reveal what happened other than that the Council abruptly disbanded the Committee and assumed control of the ground. Councillor William Watson took over. That year, he proposed another park in Ashburton on recently purchased land between Munro Avenue and Dent Street. This was promptly named Watson Park.

Cr Watson (who was now the Mayor) proved an efficient administrator and Ashburton Park had its pavilion and toilets up for an official opening on 30 October 1937. Unfortunately, I can’t find a picture of it. Ashburton State School soon began using the ground for football. By 1940, the first cricket practice nets were erected. That was the extent of the Council’s effort for the next few years. The pavilion quickly suffered from drainage issues while the ‘playground’ consisted of a desolate see-saw.

Ashburton Community Kindergarten

Then in 1945, in an effort to address the dire need for educational facilities for children in the area (see my posts on Ashburton Primary, Solway Primary and St Michaels for information on this problem) local residents Mr and Mrs Incoll mobilised the local community into creating a community kindergarten at the park.[6] A portion of the sports oval and room in the pavilion became devoted to the children.

The kindergarten was also the impetus for the Ashburton Park playground that stands there today. In the spirit of post-War frugality, everything for the new kindergarten was made by parents from waste material from the Army Reclamation dump at Fishermen’s Bend.[7] A playhouse was even made from munitions cases. The Kindergarten was an instant hit, paying off all its debt within two years.

Five years later, it had become a model for community-led kindergartens and had a 200-strong waiting list. The kindergarten moved into its own converted Army hut on Rowen Street and in December 1952, the new Rowen Street Kindergarten held its first Christmas Fair.[8]

Over the next decades, Ashburton Park became the home ground for several local sporting clubs, including the Ashburton Willows Cricket Club and the Ashburton United Soccer Club.

The Council erected the current pavilion in 1979 – so it’s probably about time for a new one!

Hartwell Sportsground

Thanks to the sustained lobbying efforts of the Hartwell Progress Association (HPA), the people around Hartwell began to benefit from some civil improvements, including a public telephone, more seating at Hartwell station, some road construction and drainage, and improved street lighting, from 1922.[9]

In 1926, the HPA announced Camberwell Council had agreed to purchase Mr Bath’s land near Bath Road for a sports ground.[10] A few years earlier, the Council had rejected an offer of land adjacent to Hartwell Primary School for this purpose, citing its cost. It had bought Bowen Street Reserve instead.

Perhaps learning some valuable lessons on dealing with the Council from their neighbours in Burwood, the HPA quickly mobilised a dedicated General Sports and Recreation Committee to lobby the Council for the development of the sports ground and the acquisition of more land around it.

‘The best way would be to have one large area with one clubhouse for all games,’ announced the Committee’s Chair, Captain T P Cook to the Box Hill Reporter. ‘Sports appeal to everybody, young and old alike. At a sports club people meet as friends, which encourages and develops a social spirit.’[11]

Thanks to the organisation of the HPA, development of the land occurred swiftly. The Hartwell Cricket Club designated the new ground as its home and set about raising funds for a cricket pitch for the forthcoming season. Within a few years, fencing and a pavilion followed.

The ground has been consistently supported by Boroondara Council and remained in use ever since. It is currently used primarily for cricket by Ashburton Willows Cricket Club, Burwood Cricket Club, Burwood District Cricket Club, Canterbury Cricket Club, and STC South Camberwell Cricket Club. The Riversdale Soccer Club also use it.

Eric Raven Reserve

This Reserve on the steep hill of High Street began its life as Glen Iris Reserve. It was originally Crown land and adjacent to the Council’s 1926 purchase of the nearby Glen Iris Park. The land sat directly on the City of Camberwell’s border with City of Malvern, divided only by Kooyong Koot (Gardiners) Creek. The City of Malvern had already begun developing the sporting grounds along the Creek so, not to be outdone, the City of Camberwell began creating a cricket pitch almost immediately. It was quickly claimed as a cricket ground by the Glen Iris Cricket Club and remains the Club’s home ground today.

From then on, like most of the parks and reserves in the 1920s, the ground suffered from neglect and vandalism. The Glen Iris Reserve Committee tried to acquire funding for a pavilion under the guise of a War Memorial but the Council rejected the plan. However, after the 1934 refurbishment of the Council, the ground received more financial attention.

I can’t ascertain an exact date the name was changed to Eric Raven Reserve but it was certainly known by it from 1965. When I did some Googling about the name, I encountered a renowned female impersonator of the 1950s called ‘Eric Raven’ and I thought for a brief moment it may have been named for him. However, that goes against absolutely everything I have ever read about the conservative and staid City of Camberwell Council. So it is far more likely the ground was named for the long-term councillor and occasional mayor, Eric William Raven (c.1903 – 1977).

According to his biography, Cr Raven was born in Malvern and worked as a shopfitter before moving to Glen Iris in the late 1920s to early 1930s. He was elected to council in 1938 and proceeded to serve as mayor three times. During his first term (1941–42) Raven officiated at the opening of North Balwyn Baptist Church. As a councillor in the 1950s he successfully fought to uphold Camberwell’s status as Melbourne’s only ‘dry’ (alcohol-free) zone. Perhaps a little conversely, Cr Raven was also a supporter of the abolition of the Council Sport on Sunday ban. That may well have been why the ground was named after him.

With the support of the Glen Iris Cricket Club and the Camberwell Lacrosse Club, Eric Raven Reserve now has a lovely pavilion and well-maintained grounds. In 2013, Boroondara Council provided $82,500 to replace the cricket nets at the Reserve.[12]

Watson Park

The site of Watson Park was first proposed by Councillor William Horace Watson (b. 15 February 1906 – 1979) in 1937. In November, Council purchased 5½ acres of land from Mr C H Meaden between Munro Avenue and Dent Street. Since Cr Watson still sat on the Council, the ground between Munro and Baird Street was quickly levelled for a cricket pitch and called ‘Watson Park’.

In the years to come, Cr Watson may well have regretted attaching his name so quickly to the marshy bog Watson Park became every winter. Nevertheless, it is fitting that Cr Watson is remembered in Ashburton as despite being *gasp* Western Australian and *double gasp* living in Balwyn at the time, he was a strong advocate on the Council for the development of Ashburton’s green spaces.

By 1940, the Council had realised Watson Park struggled with drainage when it cited the too wet conditions of the land as the reason no evergreen trees could be planted there. Things did not improve over the next decades. I’ve previously written about the dire state of Watson Park in my post about the early years of the Ashy Redbacks Junior Football Club. If you can’t be bothered reading the whole thing, here is what I said about Watson Park in the 1980s:

‘Everyone complained about the mess in the clubroom left by the Senior team. The canteen was no better. ‘We put flattened cardboard boxes on the ground [in the canteen] so the volunteers’ feet didn’t get wet,’ said former registrar Cam Johnstone. ‘It was absolutely shocking.’

Mowing the grass only resulted in the lawnmower becoming bogged and rendered the ground unplayable. The area outside the clubhouse smelt like a sewer, causing parents to freak out every time one of the kids dropped their mouthguard in the mud and put it back into their mouth.’

Boroondara Council has invested in repairing Watson Park and despite still being very boggy in winter, it remains a Cricket and Soccer ground. It also benefits from an enviable and very popular playground.

Today, Watson Park still leans towards summer sports with Ashburton United Soccer Club and the Camberwell Magpies Cricket Club basing their teams there. It is also still used for Auskick.

Markham Reserve

If you ever walked along the path at Markham Reserve wondering why there is such a large expanse of grass growing with barely any trees, ovals or other enhancement, it’s because until the 1960s the entire area was the Council’s rubbish dump. Yes, back when no-one on Council cared less about Ashburton, it was considered a great idea to dump domestic waste and old cars right next to Kooyong Koot (Gardiner’s) Creek. According to a report submitted to Boroondara Council about the site in 1997, the thickness of the waste material varied between 3 and 10 metres deep. Exactly how long it was used in this capacity is not clear but it was probably at least thirty years.

At some point in the 1960s, the dumping ceased and a layer of sand and clay was applied over the top of the landfill. This was not done in any kind of engineered way. So whenever heavy rain fell, the water soaked through. As a result, the methane gas levels generated by the rubbish underneath contaminated the soil and most likely the air around it. This restricted the growth of trees and allowed only grass to grow. The haphazard nature of the filling in of the dump also made the surface of the Reserve far too unstable to build reliable pavements and structures.

For decades the fundamental settlement problems of Markham Reserve meant it was used for passive recreation only. In summer when there was less chance of rain, cricket was played at the oval on the western end. However, winter sports teams were very reluctant to play there as it could not be certain what might emerge out of the soil after rain.

From the late 1990s, Markham Reserve was comprehensively resurfaced and renovated to address these problems. In 2010, the bike path opened, connecting the Reserve to the Anniversary Trial. This is about the time I suggested to the Solway councillor how it really needed solar powered lights. These materialised some years later probably without any regard for my request. In 2012, the Markham Reserve playground opened and quickly became so popular the Council had to build dedicated parking spaces. At the present time, an off-leash Dog Park is being prepared.

The area along Kooyong Koot Creek has also been extensively re-generated and is now a picturesque little bushwalk. At the western end is a small remnant of the Ashburton Forest. However, you can still see sickness in the shrubs and trees, indicating contaminants in the soil.

So it turns out that Camberwell Council’s disregard for Ashburton eventually resulted in a Reserve that is much admired for its large and open green space. Just don’t dig too deep to find out what is underneath!

Dorothy Laver Reserve(s)

The land along the East Malvern side of Kooyong Koot Creek came under the remit of the City of Malvern Council. It was developed into sporting grounds from at least the 1920s. Several landowners on the Ashburton side offered their land to Camberwell Council as reserve areas but as it had already been subdivided, only small allotments came available at a time.

The owners of land around Estella Street and Brixton Rise offered it to City of Camberwell as early as the mid-1920s. For the most part though, the land on the west side of Gardiners Creek was left as undeveloped paddock for several decades.

In 1975, the Council named the land after Dorothy Laver, a trailblazer on Camberwell Council. Elected in 1969, Mrs Laver defeated the South Ward incumbent of 31 years to become the City’s first female Councillor.[13] This was a time when Council elections were not mandatory and those who did vote were predominantly men.

Originally from Queensland, Mrs Laver moved to Glen Iris with her husband, who ran a secretarial services company based in Camberwell. Like many women of her era, she dedicated herself to volunteering at local schools and helped her husband in his business.[14] In 1960, she wrote a handbook called School Committees: their scope and activities that became a guidebook for parents seeking to navigate the Education Department’s regulations and procedures for establishing parents’ associations.

Two years after her husband died, Mrs Laver decided to run for Council. She became the City’s first female Mayor in 1973-4 and remained on the Council until her retirement in 1984. Mrs Laver received an Order of Australia medal in 1983.

In 1983, the Camberwell Lacrosse Club (CLC) approached Mrs Laver for her support in developing the paddocks into a home ground for themselves. Despite being one of the longest established sporting clubs in the Camberwell area, the CLC had yet to acquire a dedicated home ground, often being usurped by other sports. With Mrs Laver’s support, the club developed a plan to makeover the paddock-like fields. The successful submission to the Council included two ovals, a substantial pavilion, car-parking, a box lacrosse court, flood-lighting and a practice wall.[15]

Today, the CLC still play at Dorothy Laver Reserve East and it is also the home of the Glen Iris Dog Training Centre. The Glen Iris Cricket Club also uses the ground. The West Reserve is used by the Alamein Football Club and the Ashburton United Soccer Club.

Warner Reserve

Councillor William Warner was one of the City of Camberwell’s long-term councillors. A renowned horticulturalist, we have him to thank for single-handedly driving the planting of trees along every street in the City of Camberwell. He was elected to Council in 1932 and served two terms as mayor, one in 1937-8; the other in 1945-6, before he retired from Council in 1950. His legacy survives today in two ways: Warner Nurseries, the wholesale nursery he founded in 1914 still operates from Narre Warren; and Warner Reserve, the sports ground attached to the Ashburton Pool and Recreation Centre. While I have ragged a lot on the City of Camberwell Council in this post, I do think it is very fitting that Cr Warner has a Reserve named in his honour.

The land for Warner Reserve was purchased by Council in 1933. Cr Warner donated 40 trees for its landscaping. It originally stretched all the way to High Street and was intended to provide an oval, three tennis courts, eight (lawn) bowling rinks and a children’s playground.[16]

When it came to Ashburton, the purchase of this land was a rare forward-thinking move by the Council. At the time, the City of Camberwell’s population was doubling every year and new residents were pushing into the less developed areas on the Council’s periphery, like Ashburton. While the Housing Commission Estate built around Warner Reserve was still several years away, the space would eventually become vital to the whole suburb. However, it appears most of its recognisable development today did not begin until the early 1960s.

An ill-fated RSL Club was built on the corner of High Street that formed the precursor for dedicating that section to the elderly: Ashburton Support Services, Samarinda Aged Care, Elsie Salter House and, eventually, the new Ashburton Senior Citizens Centre. The Ashburton Lawn Bowls Club took over the lawn bowl space in the 1950s and remains there today. A large portion of the acreage was set aside for the eventual Craig Family Centre. In the late 1960s, the middle section became home to the popular Camberwell Southern Swimming Pool and eventually, the Ashburton Pool and Recreation Centre in the 1990s.

Today, the sports oval alone is considered ‘Warner Reserve’. I am hoping the trees that still remain along the street frontage were at least some of those donated by Cr Warner nearly 90 years ago.

Do you know anything further about Ashburton's green spaces? Let me know in the comments!

References

[1] "Land for Park," Argus, 29 June 1932. [2] "Complaints from Ashburton," The Argus, 20 November 1935. [3] "Move in Sunday City Sport," The Herald, 7 June 1951. [4] "Camberwell Rejects Sunday Sport," The Argus, 28 February 1947.

[1] "The Late Michael Mornane," Advocate, Melbourne, 20 August 1931. "Mr Michael Mornane," Catholic Press, Melbourne, 27 August 1931. [2] "Horses' Rest Home," Argus, 19 October 1926. [3] Lee, Neville, 'An Extended Version of the Talk on Ashburton through the Ages Presented at the Ashburton Library,' 5 September 2014.

[1] "General News," Herald, 19 January 1897. [2] Ibid. [3] "News from the Suburbs: Camberwell Parks," Argus, 1 November 1934. [4] "Park for Ashburton," Herald, Melbourne, 16 December 1924. [5] "Better Camberwell Grounds," Argus, 8 June 1935. [6] "Community Effort at Ashburton," The Age, 18 June 1945. [7] Ibid. [8] "Christmas Fair for Kindergarten," Herald, 3 December 1952. [9] "Hartwell," Box Hill Reporter, 8 October 1926. [10] Ibid. [11] "Hartwell: Sports and Recreation Club Formed," Box Hill Reporter, 12 February 1926. [12] 'Australia : More Than $3.1 Million Splashed on Boroondara Sports Facilities,' MENA Report (2013). [13] 'Tracing Her Steps: Women in Boroondara Local Goverment.' [14] According to her entry in the Boroondara Mayoral Project, available from Boroondara Library Service. [15] Fox, Doug, History of the Camberwell Lacrosse Club (2017). [16] "New Recreation Reserve at Ashburton," The Age, 22 August 1933.

Comments